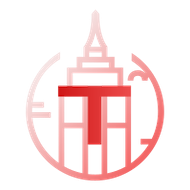

Picture above: Broadway & 72nd St in the early 20th Century

To the west of Central Park lies one of Manhattan’s premier neighborhoods. Regarded as the artsier, intellectual counterpart to its crosstown rival, the Upper East Side, it is easy to see why the Upper West Side remains a fashionable district. Both have a pleasant uniformity, with brownstones lining the streets and grand pre-war apartment buildings along the avenues. But distinctions between the two hint at the Upper West Side’s more tumultuous journey. Broadway slices through the grid, an anomaly in Manhattan’s orderly arrangement. The Lincoln Center, at the southern end of the neighborhood, and Columbia University, defining the neighborhood’s northern border, fill in blocks of the neighborhood’s grid, as does the American Museum of Natural History and NYCHA public housing projects. Perhaps most significantly, three subway lines (the {1, 2, 3}, {A, C}, and {B, D} lines) serve the neighborhood, unlike the Upper East Side, which long had only the Lexington Ave. Line (4, 5, 6), only recently supplemented by the long-awaited {Q} train extension. In these distinctions lies the story of the Upper West Side, and a story of “gentrification” before it was the buzzword of real estate and politics, a story of New York City’s ambitious northward expansion.

For Dutch settlers, colonizing this part of Manhattan was challenged by constant skirmishes with the Munsees (a subtribe of the Lenapes). Nonetheless, here the Dutch established the village of Bloemendaal, named after a tulip region town in the Netherlands and later anglicized to Bloomingdale. This land proved particularly fertile for tobacco, among other crops. Farms sprouted up in the area, and the Wickquasgeck trail, originally built by the Lenapes, was widened into Bloomingdale Road around 1703. With eased access to the city and the increased capacity of the road came more farms, and villages began to form. Harsenville and Strycker’s Bay laid to Bloomingdale’s south, Manhattanville and Carmansville to the north. Since the road ran along a ridge, wealthy residents began to settle on plantations with spectacular river views from their mansions.

Between 1790 and 1800, New York’s population doubled. It became clear that the northward expansion of the city was imminent, and the city set forth a planning commission. The result was the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, a sweeping vision of Manhattan’s grid. But with the rough terrain, especially around Strycker’s Bay (around present-day 96th and West End), and large farms, execution of the plan seemed challenging, thus remained theoretical for many.

Three major changes came in the mid-1800s. First was the creation of the Croton Aqueduct, built between 1837 to 1841. It was a monumental accomplishment for the freshwater-stricken city of New York, running roughly parallel to Bloomingdale Road. The second was the Hudson River Railroad establishing tracks along the river en route to Albany in 1846. The third was the start of construction on Central Park in 1857. These first two developments brought working-class residents and shantytowns to the area, the third removed one of the first integrated communities, replacing it with a neighborhood-defining feature. (For more about the lost village of Seneca Village, click here). But even with the construction of Central Park, which was not completed until 1876, farms still dominated the Upper West Side. In fact, because of the area’s rural character, it was thought to be a desirable location for many institutions catering to the needs of seniors and people with mental disabilities (including the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum).

Change came slowly, with Bloomingdale Road straightened bit by bit, until it became integrated with what we know today as Broadway. So when developer Edward Cabot Clark bought a piece of land on 72nd Street and Central Park West and built a luxury apartment building, it was laughed at and named “The Dakota,” for it was as distant from the fashionable part of New York as the Dakota Territory. Though Edward Cabot Clark did not live to see the Dakota’s completion, he would later be vindicated. An unlikely innovation would alter New Yorkers’ perceptions of the Upper West Side. It was the elevated train.

“in New York, we speak within limits when we say that a lady not unfrequently is compelled to wait half an hour [to cross the street]; and even then she makes the crossing at any point below the Park at her peril”

Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, June to Nov. 1854

The “fashionable” part of New York City, or the only area that resembled a city was still concentrated within a mile of the southern tip of Manhattan. It also was immensely overcrowded. These streets were plagued by traffic and horse waste (from horse-drawn stagecoaches/omnibuses and streetcars). To cross a street was to risk your life. But the undeveloped northern frontier lay far out of reach; access to the six towns of twin city Brooklyn available only by boat (Brooklyn was an independent city until 1898 when it was annexed by New York City). By the 1850s and 60s, proposals for elevated trains and underground ones abounded. After a tumultuous first few years, the elevated train staged a stunning resurgence, overcoming significant technological, political, and economic hurdles. The desperate need for mobility pushed the adoption of the elevated trains. Instead of going above Broadway, the city’s shop-lined main thoroughfare, the first “El” went over 9th Avenue (Columbus Avenue) to avoid drawing the ire of shopkeepers and omnibus companies. Click here for an excellent article from Curbed detailing the history of elevated trains (and subways).

By June 1879, the 9th Avenue Elevated came up to 81st St on the west side of Central Park, and by December 1879, it reached 155th Street. The rugged Upper West Side seemed much more palatable. It didn’t quite experience the boom of the Upper East Side; the East Side, after all, had a favorable, level terrain, which led to speculation the hilly Upper West Side will end up as the “cheap” side of Central Park. But farming certainly was falling out of fashion, with land bought up by speculators. Joining them in 1896 would be an institution that would define the neighborhood. Columbia College took a leap of faith, moving from their compact Midtown campus, taking over land that formerly housed the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum. To design their more spacious campus, they called on the esteemed architectural firm McKim, Mead, & White. In the process, the college renamed itself “Columbia University in the City of New York,” reaffirming this rural area’s rapid integration into the city. Meanwhile, their previous Midtown campus later became home of the Rockefeller Center, with the university owning the land beneath it until 1985 when it sold for $400 million.

The three towns of Harsenville, Strycker’s Bay, and Bloomingdale were towns no longer. It was all starting to come together into one homogenous neighborhood. The rockiness of the West Side began to be tamed into a grid. The iconic brownstones began to rise along the numbered streets. Columbia’s move uptown only created more speculative development in its area, turning Bloomingdale into Morningside Heights. Yet, some of these developments flailed; rubbing against these new buildings were squatters and the tenements of Irish workers who’d built the elevated lines. The uncertainty of prospective middle to upper-class homeowners of entering this new frontier next to these undesirables produced a mixed-bag of sales. Plus, the worst fears of those who opposed the elevated lines came true; streets became devoid of light, the noise deafening, the ashes destructive. Property directly adjacent to the lines fell in value. But the much craved and necessary mobility was there. Whatever the lingering doubts were about living on the Upper West Side though, would be wiped out by the next major innovation.

Riverside Drive between 93rd-94th St in 1895

94th Street in 1903

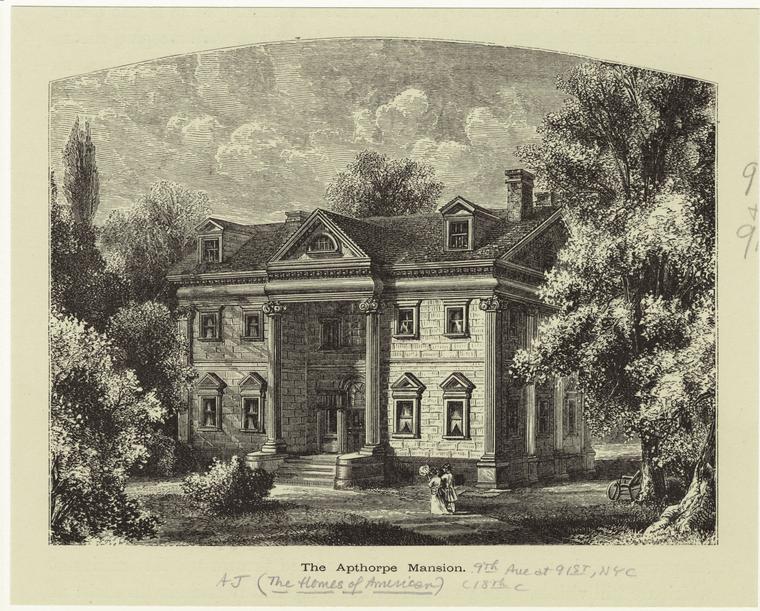

On October 27, 1904, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) opened New York’s first subway. The route went from beneath City Hall up Lexington Avenue to Grand Central, before taking a left turn to the recently renamed Times Square, then up Broadway through the Upper West Side, right past Columbia University, all the way to 145th Street. One line was all the city could afford to build at the time, and it hoped it could ease congestion temporarily. Unlike the elevated, which floundered through uncertainty, there was no questioning the subway’s success.

In the early days, lines wrapped around two blocks containing thousands waiting for their chance to ride the new novelty. It did not remain a novelty for long. Though one of the advantages of the new subway was much-increased capacity compared to the streetcars and elevated lines, within a year the IRT nearly reached its maximum of 600,000 daily passengers. Moreover, it did not provide any relief for the strained streetcar and elevated lines, which had recently been electrified (converting from horse/steam power). Within six years, the IRT was handling over 1.2 million passengers every day, more than twice its estimated capacity.

Gone was the uneven mix of development across the Upper West Side. Before, the residential development was mainly on Central Park West and Amsterdam, with Columbus Avenue the commercial center along the 9th Avenue Elevated. Now, there was a gravitational shift in growth. Once sporadically developed, Broadway became the new hub of activity with the most valuable real estate. The new IRT subway stations were all located on important cross streets connecting across Central Park (except for the since-abandoned 91st Street Station), with many businesses especially clustered around the express stations at 72nd and 96th Street. West End Avenue and Riverside Drive saw posh apartment complexes, though developers flocked to the riverfront vistas of Riverside Drive first before building more modestly on West End.

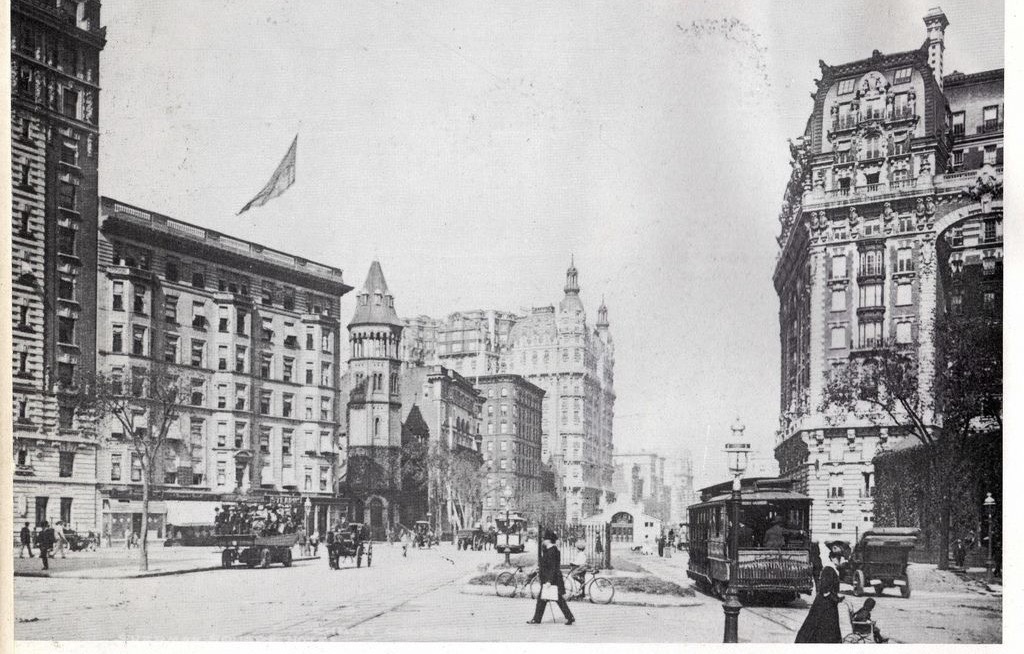

Just a few years prior, 30 of the 84 street corners between 76th and 96th Street were vacant. Even the developed land west of Columbus mainly consisted of “taxpayer” buildings, temporary structures for small businesses about 1 or 2 stories tall, built cheaply to cover costs, and reduce risk in a neighborhood filled with uncertainty. By 1916, a building boom of architectural masterpieces arose in their place, with 32 buildings of 6+ stories from 72nd to 96th Street, with eight 7-story buildings and seventeen 12-stories. Tallest among these was the legendary Ansonia Hotel, all 17-stories located on the land of the former New York Orphan Asylum at 73rd and Broadway, a building whose history is as magnificent as its facade (for more on the colorful tales of Babe Ruth’s building, click here for an in-depth feature from New York Magazine). The 79th Street Station area was dominated by the Apthorp, a full block building with a stunning interior courtyard designed by William Waldorf Astor, built in 1908 to seduce the wealthy into luxury apartment living. This was all that remained of the prominent Apthorp family, who’d owned a 200+ acre farm and a grand 1764 mansion in their name, and whose land was contentiously divvied up. On 86th Street, the Belnord similarly took up a full-block with an interior courtyard, only larger. Astor Court was the same, just between 89th and 90th, and named after another member of the Astors, the aristocratic family of the Upper East Side. The “cheap” side of the park was quickly filling up to compete against its crosstown rival. The transformation that the elevated lines and streetcars had started, but couldn’t finish, was completed by the IRT subway.

The Ansonia, in 1905.

The Apthorp in 1905

The Interior Courtyard of the Belnord, 1912

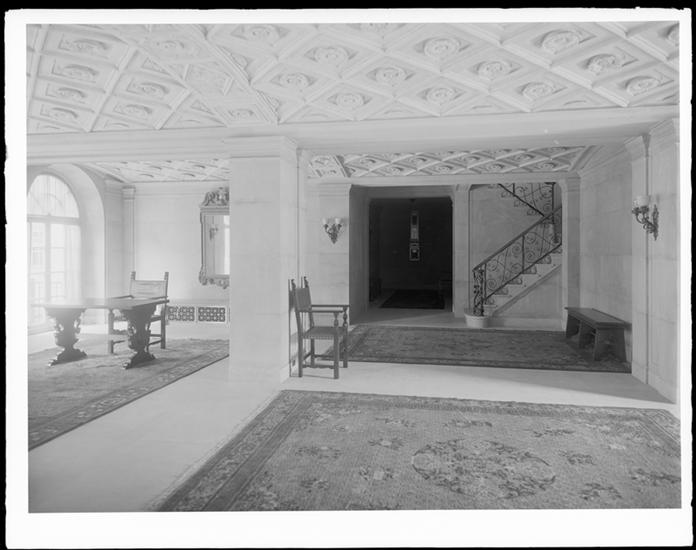

Entrance Hallway of Astor Court, 1915

Credit: Media Storehouse, Museum of City of New York

One section of the Upper West Side though was markedly different. Tucked away in the southwestern corner of the neighborhood from roughly 59th Street to 65th Street, west of Amsterdam Avenue, was the predominantly African-American neighborhood of San Juan Hill.

This name either was honoring the all-black cavalry who helped win the decisive Battle of San Juan Hill in the Spanish-American War or came from the rancorous racial tensions with the Irish gangs of Hell’s Kitchen a few blocks south. The area quickly became the most densely populated African-American neighborhood in New York City, with 5,000 people crammed into each block of tenements. Though it was the flashpoint of street wars, the area was not all about violence. In fact, African-Americans who migrated from the South and worked on the shipping docks also brought jazz to the city. Working on the water by day, they’d come up to San Juan Hill by night to wind down. Jazz, which had yet to gain traction in New York, found a foothold in these basements of tenements. It was here that James P. Johnson introduced the Charleston dance, the theme of the roaring 1920s. In the Phipps Houses, built as an affordable alternative to cramped tenements and funded by steel magnate and philanthropist Henry Phipps Jr., grew up Thelonius Monk, who developed his signature style here. The jazz that enlivened San Juan Hill lit the city on fire, and soon, New York City overtook New Orleans and Chicago as the Jazz Capital; a role it never relinquished.

Though subways were packed to its brim, the two private companies operating them were struggling to make ends meet. Limited by the “dual contracts” (public-private partnership with the city), which regulated fares to remain at 5 cents despite inflation, the city set out to take over the subways. They not only starved the companies of revenue but set out to build a competing city-owned and operated system, the Independent Subway System (IND). The IND’s first line (present-day {A, C} lines) went up Central Park West, hoping to relieve some of the pressures of the Broadway IRT subway line while taking direct aim at the 9th Avenue Elevated. Replacing their more humble predecessors were opulent new apartment buildings, such as the Beresford, Eldorado, and San Remo, which were all designed by Emery Roth and completed between 1929 and 1931 on Central Park West prior to the subway’s opening in 1932. In December of 1940, branches of the 6th Avenue Subway were connected to the Upper West Side, creating the present-day {B, D} lines. Competition from the city’s IND subway lines also brought down the 9th Avenue Elevated line earlier in 1940, while streetcar tracks disappeared beneath the pavement. Though the subway blunted some of the effects of the Great Depression, hints of the neighborhood’s demise came to light.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s entered a man with unmeasurable political ambition who’d wield his influence to forever change the Upper West Side. His name was Robert Moses. He laid his eyes on Riverside Park, first developed in 1874 along with Riverside Drive, but was nothing but a wasteland along the Hudson. Sewage, shacks, and the Hudson River Railroad tracks beleaguered the area, and Moses set off to transform this land with the West Side Improvement.

Employing 4,000 workers from the Works Progress Administration, 132 acres of parkland filled with several playgrounds, recreational fields, and a promenade were added. The train tracks were put into a tunnel, though Moses rejected a previous city-approved plan from the architecture firm McKim, Mead, and White to build a parkway over the new train tunnel. Instead, the land above the train tunnel became parkland, while he extended the shoreline by 50 feet for the parkway, inhibiting direct waterfront access. The West Side Improvement was completed in 1941, giving us the Riverside Park we know today. Though the Upper West Side benefited greatly from a beautiful, amenity-filled Riverside Park, Harlem and Upper Manhattan did not get so lucky, a fact Robert Caro dedicates a portion of his acclaimed biography of Robert Moses, The Power Broker.

Robert Moses was far from done with the Upper West Side.

San Juan Hill, which was named the “worst slum district in the city” by the NYC Housing Authority (NYCHA) in the 1940s, became Moses’ next target when he became head of the Mayor’s Committee on Slum Clearance. By then, San Juan Hill had evolved as a neighborhood. The African-American population decreased, as newer tenements in Harlem were more attractive to middle-class black residents and new migrants from the South. Replacing them was a large contingent of Puerto Rican immigrants. In 1948, the NYCHA evicted 1,100 families to build the Amsterdam Houses public housing project. In the process, they created a superblock, filling in the area from 61st to 64th Street between Amsterdam and West End Avenue.

By 1955, the stars were aligning for the ultimate Robert Moses slum clearance project. Three separate entities, Fordham University, the Metropolitan Opera, and New York Philharmonic asked Moses for a new home. With the support of John D. Rockefeller III, Moses packaged all of this together and more to create a state-of-the-art cultural landmark: the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. It took a fight to the Supreme Court to clear the path, but no one could challenge or undermine Robert Moses. In 1959, Dwight Eisenhower broke ground on the project. Over 4,000 new middle-class residences were built in the neighborhood, and not a single unit was inhabited by a former resident. Instead, the former residents were expelled to the housing projects of Harlem and Bronx, creating new slums and turning New York City into one of America’s most segregated. San Juan Hill was quite literally wiped off the map; but not before Leonard Bernstein’s classic, West Side Story was filmed in the empty streets of the neighborhood. Inspired by the neighborhood’s past, many movie scenes are shot right before and after demolition, immortalizing the memories of the area. 18 city blocks were bulldozed for the project. In 1962, the Lincoln Center Campus was inaugurated, and 7 years later the project was completed. At the expense of 7,000 families and 800 businesses, the Lincoln Square neighborhood was “revitalized.” The Lincoln Center became the home of 30 indoor and outdoor performance venues. Along with Fordham’s satellite campus, the Juilliard School, School of American Ballet, and LaGuardia High School (the city’s specialized school for visual and performing art) all call it home as well.

But at least San Juan Hill was sacrificed for something. Manhattantown, another one of Robert Moses’ “urban renewal” projects, is the subject of Chapter 41 of The Power Broker by Robert Caro. Manhattantown was to replace a thriving African-American enclave around 98th and 99th Street near Central Park. The “Old Community,” as it was known, formed in 1905 when successful black realtor Joseph Payton Jr. bought up homes on these streets to lease out to fellow African-Americans. It evolved into a model of Jane Jacobs’ tight-knit community and was home to Billie Holiday, Marcus Garvey, among others. But the low median income of the area allowed Moses to use eminent domain to clear the “blighted” land and sell it to a friend as a political favor for $1 million (the land was worth $15 million). Even worse, Moses’ friend extracted another $115,000 by ripping off tenants, never completing the project. It was sold off to another developer to finish. The poor residents were not reimbursed for their forced relocation, much less given a place to relocate to. As they fled to other poor, packed areas of the city, new slums formed before buildings were completed on the old ones.

Manhattantown was finally completed in the early sixties, over a decade after many residents were evicted. But the destruction of the “Old Community” fueled the Upper West Side’s downturn. The once-magnificent buildings of the subway boom were in a state of disrepair, inhabited by desperate rent-controlled tenants. Expansive apartments were split into smaller and smaller units. Brownstones which were built for one family were divided to house as many residents as possible. This combination of neglect, drugs, crime, and white flight left the neighborhood a shell of its former self. But new residents from all types of ethnic and religious groups, as well as a budding gay community fought to keep the neighborhood alive. Instead of the “urban decay” that took over many parts of the city and nation, passionate reform-minded, politically-involved groups organized. The artsy, bohemian flavor of the Upper West Side kept it together, and now, with the world-class Lincoln Center complex, it was sure to retain it.

From the 1970s, even as New York City began to decline, the Upper West Side was on an upward swing. Though crime still troubled the area, the eclectic mix of people made it a fun, interesting, and sometimes thrilling place to live. The people made the Upper West Side the Upper West Side, as much as the buildings themselves. But when the city was making its comeback in the late 80s and early 90s, the Upper West Side became an even more desirable place to live. For the first time, buildings like the Ansonia, Apthorp, and Belnord were getting fixed up, restoring its former glory. Chopped up apartment units were combined again to create palatial living spaces. A wealthier, glitzier clientele flocked from across the city, and even across the park. Big chains replaced mom and pop stores. Priced out of the neighborhood were the people who’d lived through the gritty days. Even the worst of the “bad” sections have become good, like the former land of the poor, but vibrant “Old Community” of African-Americans. In its place are two superblocks, housing Park West Village and the newly developed Columbus Square, consisting of “luxury” apartment buildings and retail anchored by Whole Foods Market. The very fabric of the neighborhood has changed.

The Upper West Side gentrified when the first “El” came uptown. It gentrified again with the subway. Yet again, it gentrified to become one of the safest and priciest neighborhoods today. Its buildings are impeccably maintained. It rivals and parallels the Upper East Side in nearly every aspect. Passionate residents still pride themselves on living on the right side of Central Park (which is to the left of the park). They do complain as all New Yorkers do, but fiercely profess their love for the neighborhood perhaps like nowhere else, evidenced by the numerous websites and publications dedicated to the neighborhood, from the West Side Rag to I Love The Upper West Side. However, residents can’t shake the feeling that some of its charms are getting sterilized. Do people feel nostalgic about the violence and danger of the 50s? No. But as its quirks are ironed out, Upper West Siders ponder what the future holds for their neighborhood. One of its anchors tells a cautionary tale.

The Lincoln Center is a beloved cultural institution of New York that also fosters some of the greatest artistic talents. Its iconic water fountains and welcoming front steps open out to Columbus Avenue, an invitation to the public to come enjoy and admire its treasures. But the complex also literally turns its back to the public housing projects and the neighborhood it left behind. We can only hope that the Upper West Side doesn’t turn its back on its beloved idiosyncrasies, and unlike the ghosts of San Juan Hill, that the uniqueness of the Upper West Side endures through the ever-changing nature of New York City.

For those interested, some further reading…

- Our profile on the history of Seneca Village, the lost African-American settlement of Central Park

- Excellent features from the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group

- History of Elevated Trains (and subway) from Curbed

- A short history on the Ansonia from New York magazine

- Nora Ephron on living in the Apthorp in New York magazine

- The Power Broker by Robert Caro

- West Side Rag and I Love The Upper West Side, two staple publications of the Upper West Side

- West Side Story filming locations

Kai Oishi

Evolution of NYC