“One entered the city like a god. One scuttles in now like a rat”

Vincent Scully – Yale Univ. Architectural Historian

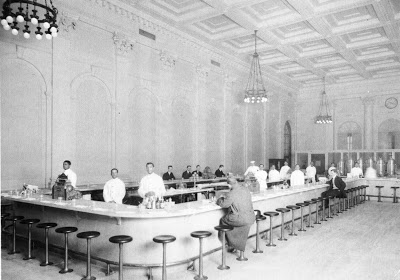

On November 27, 1910, the world awed at the opening of a monumental building; one that not only imitated but rivaled the great works of Ancient Greece and Rome. It was the gateway New York deserved; the world’s largest building built in one go and perhaps its finest. Combined with 16 miles of tunnel work going underneath the Hudson and East River, the visible and invisible aspects of the project made the completion of Pennsylvania Station the most significant engineering feat of its time. Even St. Peter’s nave paled in comparison to the length of the station’s waiting room; it’s height nearly matched the Coliseum’s at ~150 feet. 100,000 people from around the world came to see this new landmark on that day, on top of 25,000 passengers; visitors openly sobbed at its beauty. One could only feel that it was the start of a new era. But 53 years later, a demolition crew descended upon the station, tearing down every last remnant of its elegance. Ironically, its destruction is what truly ushered in a new era of impassioned preservationism in New York.

The Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) had a late start. Created in 1846, nearly 20 years after its main competitors (Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and a few NYC railroads that later merged into NY Central), it nonetheless rose to the top as one of the major players in the railroad industry. The popularity of the railroad, along with New York City’s growing prominence put the two entities on a collision course. By 1871, the PRR could sniff the island of Manhattan from its Exchange Place station in Jersey City. But going the last mile into the city was impeded by the insurmountable barrier that was the Hudson River. This meant passengers had to make a mad dash to the ferries which departed every 10 minutes from the west bank of the river, threading past hundreds of other ships, on its journey into Manhattan.

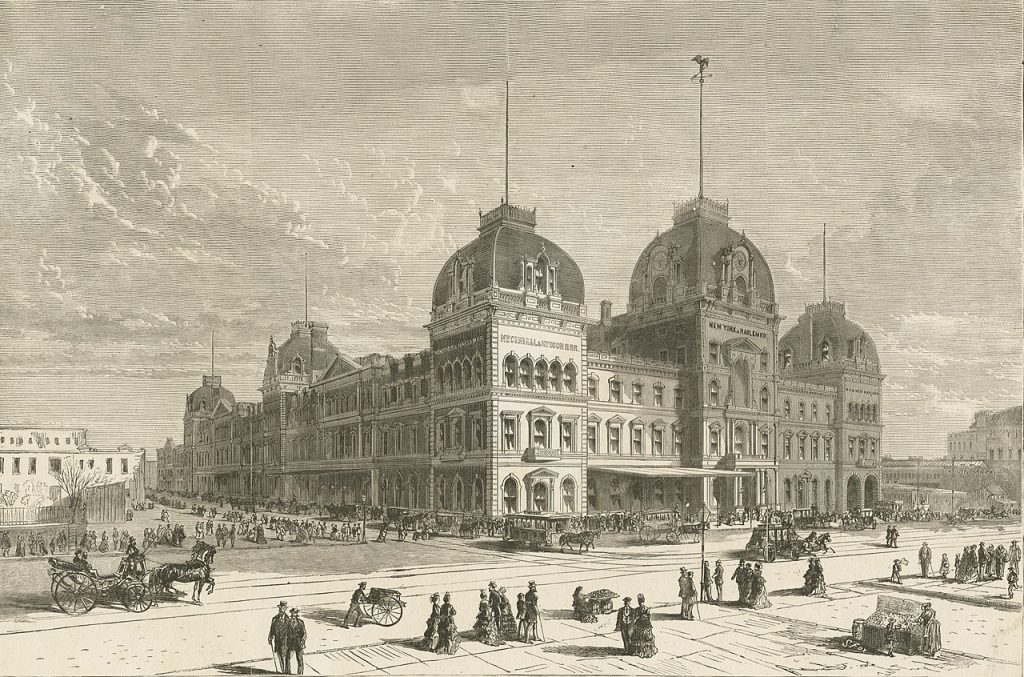

Cornelius Vanderbilt’s Second Empire masterpiece

Meanwhile, Cornelius Vanderbilt had wielded his power and money to consolidate three railways into one, bringing them into one station on 42nd Street in 1871; Grand Central Depot. Its immense success forced expansion in 1900; in turn, the building was renamed Grand Central Station. The station and direct access to the city was the envy of PRR president Andrew Cassatt.

It was simply unacceptable to have the largest railroad in America, yet not directly connect with America’s commercial hub. But he was stuck: a deal between rival railways to build a bridge across the Hudson collapsed as its astronomical price point of $27 million (~$770 million in 2020) proved untenable. But a tunnel had challenges as well. At the time, it was believed to be impossible to bore a tunnel beneath the Hudson. Even if you managed to do so, putting steam locomotives through a tunnel impairs the vision of the driver and can cause asphyxiation. But Cassatt found a solution when visiting his sister in Paris in 1901; electric locomotives. Taking three days to study the newly completed Gare d’Orsay and the technology involved, Cassatt returned to America reinvigorated.

A tunnel it would be. The PRR went ahead to purchase the Long Island Railroad, to consolidate the two at one station. Then, to keep land prices low, the PRR went door to door, buying up property by property, until they secured 7.5 acres of real estate for its Manhattan station, laying between 7th and 9th Avenue, from 31st to 33rd Street. The Tenderloin District, as it was called then, would lose 500 of its buildings and thousands of African Americans in the process. But at last, the groundwork was set for Cassatt’s grand vision.

But to compete with the then Grand Central Station of Vanderbilt, Cassatt needed to build more than a train station. So he called on the best architectural firm there was: McKim, Mead, & White. Fresh off of completing Columbia University’s newly built campus in Morningside Heights, and other significant works including the Arch of Washington Square Park, Brooklyn Museum, and the Boston Public Library, Penn Station would rise above them all to become the firm’s most renown project. The Acropolis of Athens, Rome’s Baths of Caracalla, Gare d’Orsay of Paris (but twice as large), and the Crystal Palace of London were among the inspirations for the new station.

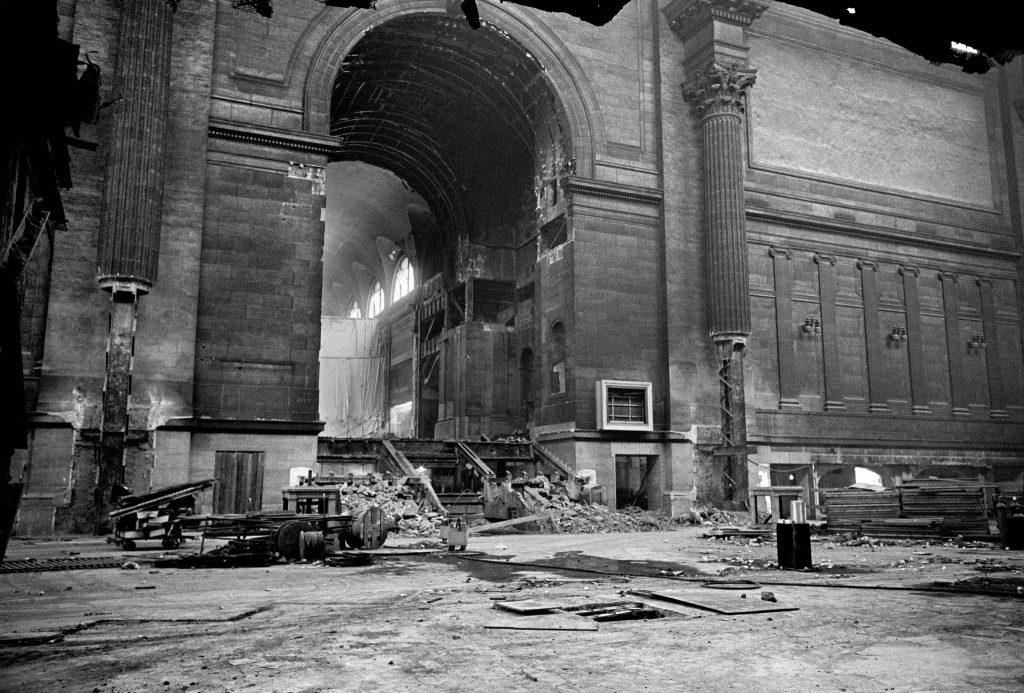

The construction of the station began in 1906. 27,000 tons of steel, 500,000 cubic feet of granite, 83,000 square feet of skylights, 17 million bricks, and 4 years later, it was done. Neither Cassatt nor Charles Follen McKim lived to see its completion; Cassatt died in 1906, McKim in 1909. But the two’s tireless collaboration left Penn Station as the proud legacy they’d left behind. The finished product was certainly a sight to behold. 84 granite columns adorned the building. An expansive atrium with a wrought-iron and glass roof. 22 eagle sculptures, weighing 5,700 lbs each, welcomed passengers at each entrance, symbolizing the railroad’s conquest of new territory.

“Penn Station did not make you feel comfortable; it made you feel important.”

– Hilary Ballon, NYU Art Historian

The station was a smashing success. 1,000 trains per day proved too few, and 11 weeks into service, the revised schedule added 51 daily trains. 18 million passengers used Penn Station in the following year. It was built to be a palace for the people; a public space for them to use and feel important, feel like they were in the center of the universe. For the Pennsylvania Railroad, they didn’t feel it; they were the center of the world. The PRR was “the Standard Railroad of the World” and “a nation into itself.” It was the largest publicly traded corporation with a budget only second to the U.S. government, giving shareholders dividends 100 straight years (which remains a world record).

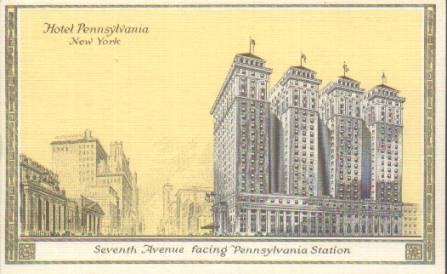

The adjacent neighborhood would see two more McKim, Mead, and White designed buildings: the General Post Office Building (now the Farley Building) completed in 1912, and the PRR’s Hotel Pennsylvania, which opened in 1919. It too was the largest hotel in the world, with 2,200 rooms, and was revolutionary, just like the station. The hotel was operated by E.M. Statler, whose motto “the guest is always right” and dedication to efficiency immortalized him as an innovative hotelier.

Though Grand Central Station underwent its own teardown, rebuild, and renaming to Grand Central Terminal in 1913, not even Vanderbilt could outdo the PRR. Whenever the President of the U.S. or any world royalty came to New York, they came through their platform on Penn Station’s track 11 and 12. Soon enough, they’d get a direct connection with the newly built IRT Broadway-7th Ave. Line (current 1, 2, 3). The line, constructed in 1917, linked South Ferry to Times Square, where the line extended to the Upper West Side, Columbia Univ. to Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx. Penn Station’s other subway, the IND 8th Ave. Line (Chambers St. to 207th St., A, C, E) came in 1932. Additional improvements (ex. electrification) and expansion of the Long Island Railroad section of the station came to the station in the following years.

Yet as the PRR flourished, and the station saw its billionth passenger in 1935, the station’s size and grandeur made maintenance challenging. The same Italian pinkish travertine marble used for the Roman Baths were now coated by New York grime. By 1945, 100 million passengers a year went through Penn Station, with 144 trains per hour on their 21 tracks, going in every direction on PRR’s 10,000 miles of track. As more time passed, the station deteriorated. In 1947, PRR reported its first operating loss ever. The hundreds of billions of dollars the government poured into the Interstate Highway System and subsidies for airlines helped fuel their rise and the railroad’s decline. Even the mightiest were vulnerable. In 1956, a $2 million modernist, Eero Saarinen-esque ticket counter designed by Lester Tichy was installed in the main waiting hall. Whether it was an attempt to revive the station with a sleek design or to hasten the Beaux-arts building’s demolition, we cannot be sure. Nonetheless, with the PRR’s demise, a last-ditch attempt to save the railroad sprung out to destroy its costliest, most valuable asset.

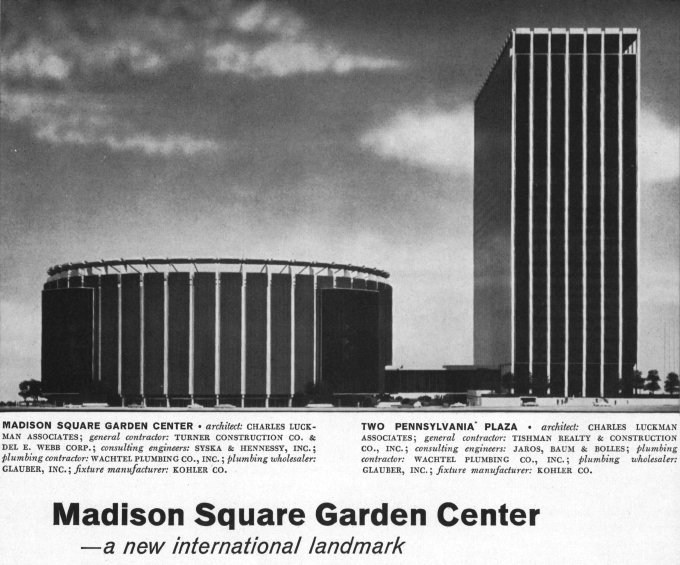

No one could save Penn Station. Not any law, not any number of architects or protesters. Though it was built for the people and used by the people, the PRR owned it, and if it wanted to destroy it, they could. Nothing could stop the capitalist forces from wrecking through the besmeared splendor of the building. Some justified it as a progressive act for the dying railroad industry. Anyways, the essentials of the station, the tracks and platforms, laid below ground. For its air rights, the PRR would get a new, air-conditioned, basement station for free. Where billions admiringly waited and wandered en route to their destination, was to be razed for the railway’s 25% stake in the replacement complex. A monument for the ages barely stood for half of a century; its noble columns found itself ignobly “buried” (dumped) in the swamps of New Jersey.

“Until the first blow fell, no one was convinced that Penn Station really would be demolished, or that New York would permit this monumental act of vandalism against one of the largest and finest landmarks of its age of Roman elegance.”

The New York Times: “Farewell to Penn Station” – October 30, 1963

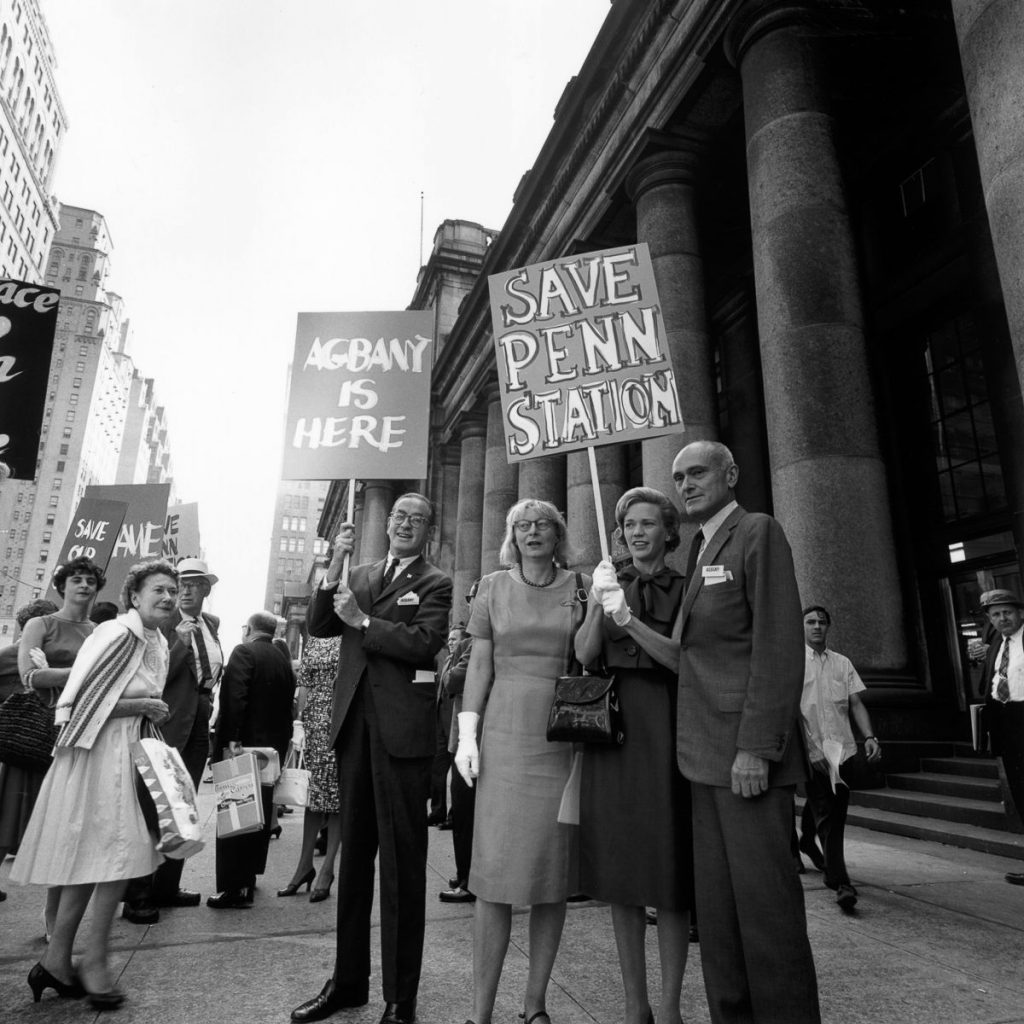

Many couldn’t fathom how Penn Station, their beloved Penn Station, could be so unceremoniously torn down. It was not an easy feat to knock down and build above it; it required another engineering feat to put a large steel deck to cover the tracks and platforms. But it could be done. The outrage sparked worldwide and certainly in New York City single-handedly ignited the once-radical preservationist movement. It was mainstream now. In 1965, New York City created the Landmarks Preservation Commission, two years after the first hammers chipped away at the magnificent columns of the station, and before the station’s demolition was even finished.

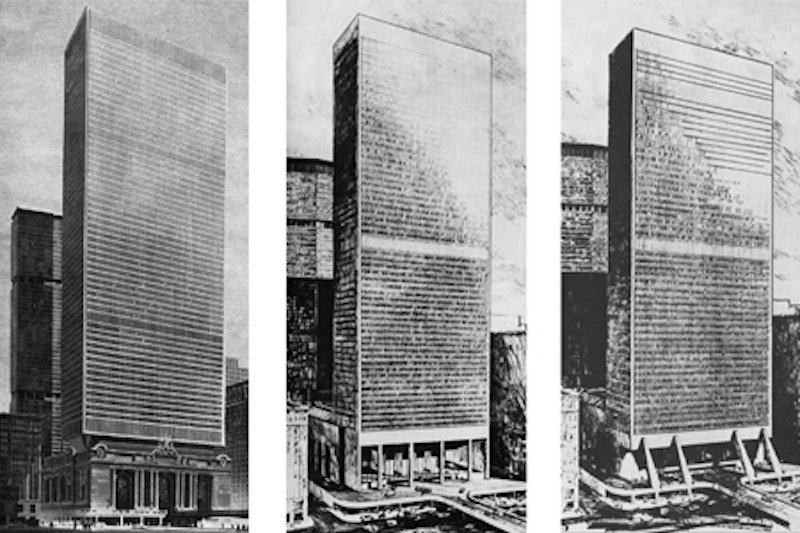

The final twist in the original Penn Station’s legacy would come in 1968, the year the Madison Square Garden finally opened. The Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central Railroad Vanderbilt had owned, both coming down on hard times, merged into the Penn Central. This new company now owned Grand Central Terminal and a familiar proposal arose. Penn Central wanted to demolish Grand Central to build a 53-story office building. New York City could not tolerate the murder of its other landmark station. Everyday New Yorkers banded with celebrities like Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, to save the building. 11 years and a Supreme Court decision later, it was finally put to rest. The landmark law survived. Penn Station once built to outrival Grand Central, died to see it live.

Many predicted the death of railroads. Though Penn Central and its fellow private railroads disappeared, train travel has made something of a comeback against all odds. What the PRR built remains the lifeline of the region. Even then, its long-neglected infrastructure is now crumbling, plaguing the railroads. Every New Yorker is humiliated by today’s Penn Station, the embodiment of the sad state of American railroads. The subterranean station was only designed for 200,000 passengers per day. But 650,000 people every day are relegated to dimly-lit passageways that suffocate below Madison Square Garden. The tunnels, platforms, and tracks that serve the station have been over capacity for years, yet have barely changed since 1910. No new train tunnels have been built beneath the Hudson for over 110 years, as proposals to relieve them have consistently stalled. Since the 1990s, there has also been talk of fixing and expanding Penn Station into the neighboring Farley Post Office building. Most call for tearing down Madison Square Garden. Alas, only small parts of the plan have been executed, while the rest of it languishes in political purgatory. It seems the ambition, vision, and will of Cassatt and McKim have all but vanished.

“The tragedy is that our own times not only could not produce such a building, but cannot even maintain it”

“How to Kill a City” by Ada Louise Huxtable for the New York Times; May 5, 1963

At the height of the controversy over the impending destruction of Penn Station, Irving M. Felt, President of the Madison Square Garden Corporation said “the gain from the new buildings and sports center would more than offset any aesthetic loss…Fifty years from now, when it’s time for [Madison Square Garden] to be torn down, there will be a new group of architects who will protest.” Fifty years have come and gone since that day, and it is safe to say, not another one passes where New Yorkers don’t lament what has become of Penn Station.

“Any city gets what it wants, is willing to pay for, and ultimately deserves. Even when we had Penn Station, we couldn’t keep it clean. We want and deserve tin-can architecture and tin-horn culture. And we will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those that we have destroyed.

The New York Times: “Farewell to Penn Station” – October 30, 1963

Kai Oishi

Evolution of NYC

Works Cited

Pennsylvania Railroad, www.cs.mcgill.ca/~rwest/wikispeedia/wpcd/wp/p/Pennsylvania_Railroad.htm.

“Long Island Trains Inaugurated Service from Pennsylvania Station 25 Years Ago.” Fulton History, Long Island Press, 8 Sept. 1935, fultonhistory.com/Newspaper%2014/Jamaica%20NY%20Long%20Island%20Daily%20Press/Jamaica%20NY%20Long%20Island%20Daily%20Press%201935/Jamaica%20NY%20Long%20Island%20Daily%20Press%201935%20-%205070.pdf.

Beschloss, Michael. “Penn Station: A Place That Once Made Travelers Feel Important.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 3 Jan. 2015, www.nytimes.com/2015/01/04/upshot/a-place-that-made-travelers-feel-important.html.

“Farewell to Penn Station.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 30 Oct. 1963, www.nytimes.com/1963/10/30/archives/farewell-to-penn-station.html.

Huxtable, Ada Louise. “ARCHITECTURE: HOW TO KILL A CITY; Ours Is an Impoverished Society That Cannot Pay for the Amenities Joker Impotent Authority Radical-Picturesque For the Worse.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 5 May 1963, www.nytimes.com/1963/05/05/archives/architecture-how-to-kill-a-city-ours-is-an-impoverished-society.html.

Kimmelman, Michael. “When the Old Penn Station Was Demolished, New York Lost Its Faith.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 24 Apr. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/04/24/nyregion/old-penn-station-pictures-new-york.html.

“Pennsylvania Station.” American, www.american-rails.com/pnstn.html.

“The Romance and Pain of Penn Station.” (What Is This? Blog), parenthetically.blogspot.com/2010/10/romance-and-pain-of-penn-station.html.