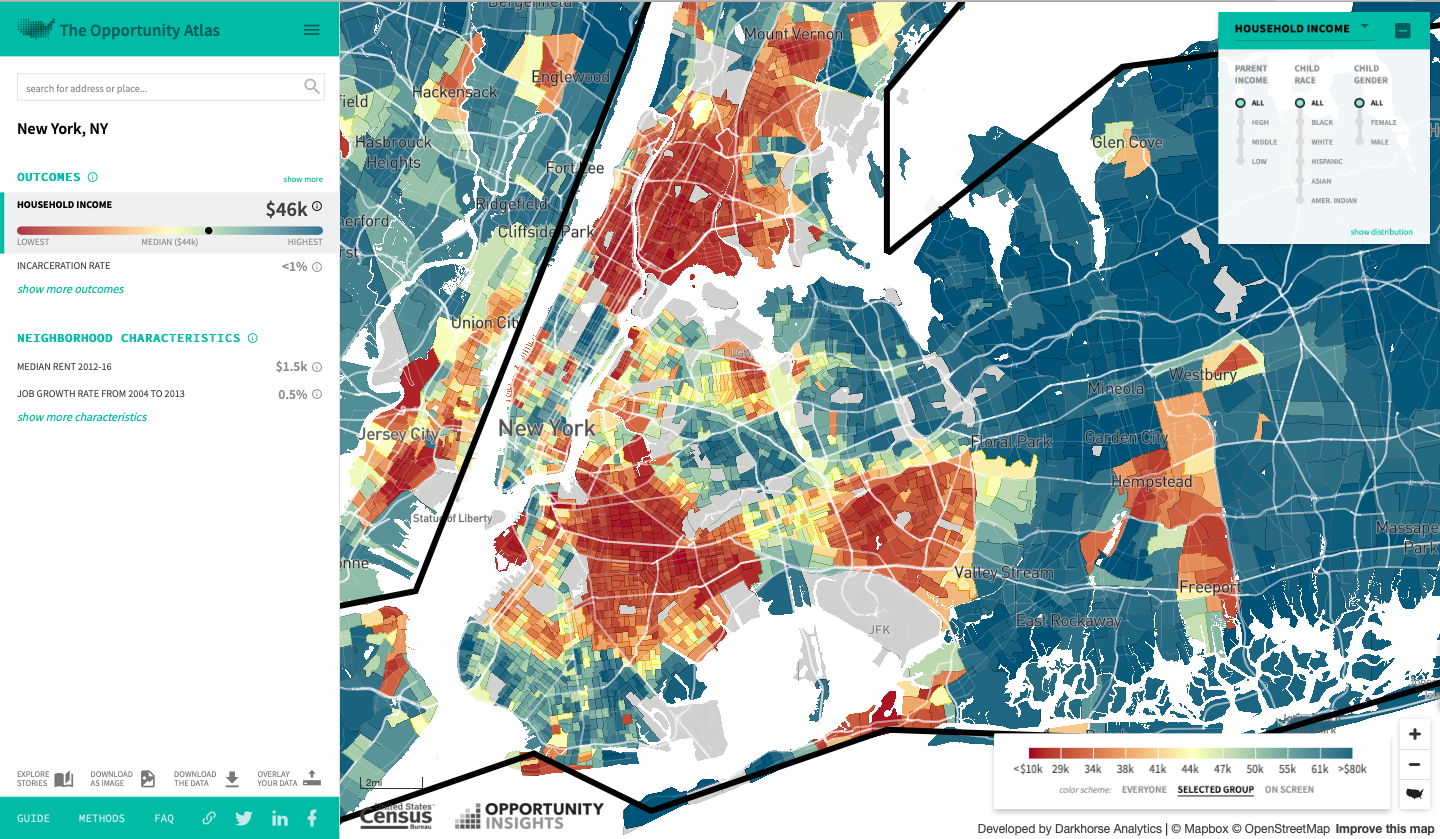

Above, use the slider to compare the two images. On the left is a map of economic opportunity (upward mobility) from The Opportunity Atlas. On the right is a racial dot map. For the full screen version of this image, click here.

New York has long been a welcoming entry point for all people from all backgrounds. Whether it was immigrants from various countries entering through Ellis Island and sailing past the Statue of Liberty, or African-American migrants fleeing the South to seek a better fortune, New York City has always been the place to come. As of 2018, 3.1 out of the city’s 8.4 million residents are immigrants (about 38% of the population and 45% of the workforce), and is a majority-minority city, meaning minorities (Black, Hispanic, Asian, Multiracial, etc) make up a majority of the population (~57%, as opposed to ~43% white).

But disturbing trends have led the city on two divergent paths; one for the wealthy, one for the poor, a divide that follows starkly along racial lines.

The Occupy Wall Street movement of 2011 foreshadowed some of the pent-up frustrations that propelled then-unknown mayoral candidate Bill de Blasio into City Hall in 2013. De Blasio often spoke of “a tale of two cities,” with his rallies against rising income inequality surging him from 4th place in the Democratic Primaries to the biggest landslide victory in a mayoral race in nearly 30 years.

Yet, even de Blasio and his most ardent supporters will admit that the challenges are bigger than anyone could anticipate, and progress much slower than they hoped. His popularity has declined as confronting these systemic problems have sparked controversy and contentious debate. Gentrification is a hot button topic, as both longtime and lower-income residents are burdened by rapidly rising rents, outpacing their wages, at risk of losing their homes to more affluent residents. Meanwhile, the city is home to some of the poorest, most segregated neighborhoods in America, as the demand for housing, especially for working and middle-class families, has far outpaced the supply, leaving nearly half of New Yorkers rent-burdened, and record numbers homeless. The housing crisis goes hand in hand with the most segregated public school system in the U.S. and the city’s most polarizing issue. At Stuyvesant High School in 2019, arguably the city’s top high school, 895 students were admitted. Just 7, 0.78% were African-American, despite making up about 26% of the general student population. The disparity in opportunity can be seen by students three miles apart (Watch this NYTimes’ Weekly Episode and listen to NPR’s This American Life feature) or even just across the street (read more in my article, Catalysts of Change: Chelsea Markets+High Line and watch Class Divide).

“Can anyone look the parent of a Latino or black child in the eye and tell them their precious daughter or son has an equal chance to get into one of their city’s best high schools?”

Mayor Bill de Blasio in a 2018 op-ed on specialized schools

Public housing projects from the days of “urban renewal,” all built around the same time, are now all critically falling apart at the same time. It is a miracle that the subway, the backbone of New York and a ticket of opportunity for all residents, can ever function after the century-old system faced decades of neglect (“deferred maintenance” in political-speak). It has been in a state of emergency since 2017.

Simultaneously, Wall Street rose out of the ashes of the financial crisis of 2007-2008 stronger than ever, a luxury apartment boom has hit every part of the city, with a new “Billionaires’ Row” casting shadows upon Central Park, and Hudson Yards, America’s costliest real estate development ever, dubbed a “playground for the rich.” Today’s New York is a city in crisis, one that has been decades in the making. The coronavirus pandemic has only exposed this even more. How did New York get to this point, why did it happen, and what does the future hold for a city that has long proclaimed itself the world’s “greatest” city? To fully understand the problems of today and the polarizing politics behind it, we must take a look at the stories of the past.

It goes without saying that the roots of racism go far beyond what this spotlight feature will cover and focus upon. When the Dutch arrived in 1624, colonizing Lenape land to settle “New Amsterdam,” it began a two-century long ouster of the indigenous people from their land. Over time, the Lenapes, which inhabited the Greater New York City area, were pushed out. Most were killed, but if they were lucky, they were removed and eventually relegated to reservations in Oklahoma and Wisconsin, as well as Ontario, Canada.

Two years later, in 1626, the first slaves arrived in New York. Slave trade flourished, later centering around a slave market created on Wall Street in 1711, the beginning of the street’s economic importance. Even as slavery was “phased out” in the following years, New York City’s deep ties with the South and its slave economy made the city a Confederate hotbed in the North. The Erie Canal, opened in 1825, turned New York City into America’s leading port, and the city’s economy and importance was dependent upon cotton from the South going through the city en route to the textile mills of the North. Illegal slave trade continued through the city until the Civil War’s end, and the mayor of New York at the time, Fernando Wood, proposed seceding from the Union for the Confederacy. Racial tensions culminated in the Draft Riots of 1863, where predominantly Irish immigrants pillaged the city, murdering black residents in the streets, and burning down homes of abolitionists and an African-American orphanage.

The Civil War ended with the Confederacy’s defeat in 1865, but segregation and racial hostility persisted. New York City’s rise as a global center came in these post-Civil War years. From 1860 to 1890, both the overall population and immigrant population roughly doubled. About 12 million immigrants sailed into the city via Ellis Island, passing by the Statue of Liberty along the way. Ethnic enclaves formed, as new immigrants were helped by more-established countrymen. The Brooklyn Bridge was completed in 1883, connecting New York with its twin city, Brooklyn, by land. This led to the city’s annexation of Brooklyn in 1898, integrating it into New York City, doubling its population again. Meanwhile, the elevated lines opened up new areas of Upper Manhattan in the early 1880s, imprinting the grid on the rest of the island. Central Park fully opened up in 1876, giving New Yorkers a respite from the hustle and bustle of the city, while the first Upper East Side elites emerged, building their lavish Gilded Age mansions up along 5th Avenue.

From 1900 to 1940, as New York City’s population more than doubled yet again, from 3.4 million to 7.5 million. Along the way, New York City overtook London as the world’s most populous city in 1925. Facilitating the boom was the massive expansion of the subway system during this time. The first line was built in 1905, and many more followed. Early lines were built by two companies, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) and Brooklyn Manhattan Transit Company (BMT), under public-private “dual-contracts.” These two separate systems sprawled all across the city, turning farmland into blocks of apartments and tenements almost instantaneously. They also had different sized trains, platforms, and tunnels, which were incompatible, foreshadowing the challenges that the city would face in maintaining the complex system. Soon, a third, city-owned and operated system, called the Independent Subway System (IND) opened in 1932. Discontent with the overcrowding subways (and perhaps because then-Mayor Hylan had previously worked for the BMT…and got fired), the IND had a different goal than previous networks. Instead of expanding outwards, the IND filled in gaps of services and competed against the other subway and elevated lines. The IRT and BMT, financially limited by the city-mandated five-cent per ride fare (which remained unchanged since its inception, despite inflation), eventually were bought out by the city in 1940, creating a unified system. In December of 1940, the Sixth Avenue IND Subway (the {B, D, F, M} lines) opened. Construction on the long-awaited Second Avenue Subway was expected to start soon after. But the ambitious plans of 1929 and 1940, visions of a city where no resident lived outside a walking distance of a subway station were shattered by the Great Depression and World War II. Where subway lines were and were not built dictated the development of each area and had profound impacts on where people live and the opportunities they are afforded. Since 1940, no new lines have been built, with only modest extensions completed.

Though the subway opened up new areas to live and work, not everyone could live everywhere. The legacy of Jim Crow-era policies is their direct impact on the housing and school segregation of the present-day. The term “redlining” literally comes from Federal Housing Authority maps of the 1930s, where African-American neighborhoods were noted as “hazardous” and marked in red. This prohibited them from getting federally-backed loans. Neighborhoods without “a single foreigner or Negro” were marked in green, allowing fully backed mortgages in those areas. In between were blue areas that were “still desirable” and yellow areas, usually categorized as “definitely declining” due to the “infiltration” of colored people and a “lower grade population.” Redlining prevented large swaths of African-Americans and other minorities from ever buying a house, the key to building equity and moving up in society. “Good” neighborhoods were off-limits. They were denied even an opportunity at the American Dream. Instead, the labels became self-fulfilling prophecies. What followed was disinvestment and the downfall of these neighborhoods and the city of New York.

Above: An Interactive Map of “Redlining” from the University of Richmond’s Digital Scholarship Lab (follow the link for a better viewing experience)

Another major factor: “urban renewal.” A polite-sounding policy, urban renewal was anything but that. Its champion was Robert Moses, the master-builder of New York. Razing blocks upon city blocks, the idea was to clear “blighted” areas and replace them with federally-funded middle-income housing projects. The result? Tight-knit, predominantly African-American and Puerto Rican neighborhoods like San Juan Hill and the “Old Community” (Manhattantown), both on the Upper West Side, were literally wiped off of the map. In the name of “slum clearance,” It is estimated that ~500,000 New Yorkers lost their homes through urban renewal, a larger population than Atlanta, Denver, Memphis, or Phoenix at the time. As James Baldwin said, “urban renewal…means negro removal.” Few were able to live in the apartments that replaced them, either explicitly forbidden because of their skin color, if not, unable to afford them. Forced out of their homes and with no money and no place to go, they had no choice but to further pack into carved-out rooms in tenement buildings in the deteriorating areas of Harlem, Bronx, and Brooklyn, which were suffering the effects of redlining. Through urban renewal, more housing units were destroyed than built, and faster than the old “slums” were cleared, new, more concentrated slums formed in different parts of the city.

With segregated neighborhoods came segregated schools. School segregation had technically been abolished in the State of New York in 1920, but school zoning entrenched the effects of minorities relegated to redlined areas. Even though Brown v. Board of Education ruled that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” in 1954 and integration efforts followed across the nation, New York City never integrated. A decade after the decision, the lack of integration fueled the largest civil rights protest of the era, with more participants (~460,000) than the March on Washington (~250,000). But backlash came swiftly when the white and mostly female “Parents and Taxpayers” group marched across the Brooklyn Bridge to City Hall a month later against busing and other integration efforts (they were named “Parents and Taxpayers” to assert their higher status over minorities who were also parents and taxpayers). Even executing small parts of the Board of Education’s integration plan were met with vitriol, and the “massive resistance” that had so characterized Southern white families’ fight against desegregation that ended mostly in failure, had succeeded in New York. The integration plan slowly dissolved as pressure mounted, debates persisted, and the 60s turned into the 70s. A different battle spun off in the early 70s, regarding the city’s top high schools. Debates centered on the Specialized High School Admissions Test (SHSAT), proposed to be the sole requirement to enter the city’s top schools. The New York Times reported, “The brief but spirited fight culminated in May 1971, when members of the New York State Assembly shouted each other down, lobbing accusations of racism and bias, before ultimately approving the bill.” It seems that not much has changed, as school segregation and the SHSAT remains a point of contention today, half a century later, as debates on race and opportunity ignite students, parents, and politicians.

“I do not blame the two distinguished Senators from New York, for they desire to protect New York City, as well as Chicago, Detroit, and similar areas… In my opinion the two Senators from New York are, at heart, pretty good segregationists; but the conditions in their State are different from the conditions in ours.”

James O. Eastland; Mississippi Senator, 1964

Over the twenty years following World War II, the city saw the construction of many large infrastructure projects. But the city’s miraculous growth story had ended in 1950 after subway ridership peaked in 1946. After half a century in operation, the subway started to show its cracks. Robert Moses, at one point holding 12 separate unelected offices, used his influence to gather a lion’s share of state and federal funds for infrastructure. As Robert Caro explains in The Power Broker, it was enough money to modernize the subway and the Long Island Railroad, and fully build out extensions like the Second Avenue Subway the length of Manhattan, and build extensions to connect hundreds of thousands of Queens and Brooklyn residents without subway access, and build a trans-Hudson loop with two tunnels to New Jersey. But not a cent of the money Moses controlled went towards public transportation; instead it went towards highways, bridges, and tunnels. Some, like the Cross-Bronx Expressway, decimated communities, with Robert Caro going into painstaking detail about the effects of one mile, the most expensive mile of road ever built, on the East Tremont neighborhood (read an excerpt of Caro’s “One Mile” chapter of The Power Broker here). The expressway finally was completed in 1972. By then, arson was sweeping through the borough as slumlords found it more lucrative to gather insurance money from burning down their buildings than to renovate or sell them. 7 Bronx census tracts lost over 97% of their buildings to fires, 44 more lost over 50% of their buildings, out of the borough’s 289 tracts. The South Bronx lost 60% of its population. It was defined by desperate poverty and high crime. The brutal impact of years and years of slum clearance, urban renewal, redlining, and segregation brought the Bronx and the city as a whole to its lowest point. The subway was crumbling, graffiti-covered, and shrinking (some subway lines were in such bad shape, they were abandoned, reducing the subway’s size). The city was hollowed out. New York was bankrupt.

The dark days of New York City lasted until the late 1980s and early 1990s, though the foundation for its recovery was set before then. It began with Mayor Ed Koch who balanced New York’s budget in the early 1980s as he kickstarted gentrification efforts. NYC Transit Authority (NYCTA) President David Gunn rid subway cars of graffiti and began long-overdue repairs to the system. But the comeback path was never that simple. The crack epidemic and illegal drug trade flourished, homelessness abounded, crime ruling the subway, and the city. The Central Park Jogger and Bernard Goetz’s subway shooting (“the subway vigilante”) defined the decade. Koch’s brashness, enduring to New Yorkers for three terms, wore off as divisive and arrogant. He had won the Democratic and Republican primary for the mayoral election of 1981, but his bid for a fourth term ended when he lost in 1989 to David Dinkins in the Democratic primary. Dinkins narrowly defeated Rudolph Giuliani to become New York’s first (and to this point, only) African-American mayor. Dinkins left a complicated legacy. The crime rate actually went down for the first time in 30 years during his time, but the 1991 Crown Heights riots damaged his reputation. His tax hikes were unpopular, though they provided funding for the subway and expanded the police force and their training. A nationwide recession didn’t help, and a voting surge in 1993 of Staten Islanders who wanted to secede from the city (which the state ultimately blocked) propelled Rudy Guiliani into City Hall by a razor-thin margin. Campaigning on “law and order,” Giuliani spent four years after his loss stoking the fears of New Yorkers and encouraging racist rants aimed at Mayor Dinkins, even rallying white policemen against him. It worked. (Read more about “Rudy’s Racist Rants” from the libertarian think tank Cato Institute)

“ Now you got a n***** right inside City Hall. How do you like that? A n***** mayor.”

Off duty policemen at a riot in front of City Hall in 1992, during Mayor David Dinkins’ tenure. He was New York’s first (and to this date, only) African-American mayor

Giuliani’s legacy is twofold; New York emerged from the darkness fully asserting its place in the spotlight as a “shining city of a hill,” but this sometimes overshadowed the splitting path he put the city on. He “Disneyfied” Times Square, but public housing projects were defunded. The subway system finally recovered from the depths of the 70s and 80s, only to receive massive budget cuts in the mid-1990s. Crime went down, but so did his approval ratings as his unequivocal support of the police and racial profiling tactics in the wake of the brutal assault of Abner Louima (one of the cops from the case is employed by the city and makes six-figures) and shootings of Amadou Diallo, Gidone Busch, and Patrick Dorismond made him a widely-despised figure among minorities. He was widely praised for his response to 9/11 and nicknamed “America’s Mayor,” though his approval ratings among African-Americans went down to 6%, with 91% disapproving, while his overall ratings dropped precipitously low after the murders and before the tragedy.

The subway’s state of emergency in 2017 (and continues to this day) directly traces its problems back to the massive budget cuts of the mid-1990s at the hands of Giuliani and fellow Republican Governor George Pataki. Just as the subway system had recovered, it was abandoned. Budget cuts left the agency with no choice but to defer fixing critical infrastructure. Even worse, in 2000, Wall Street powerhouse Bear Stearns swindled the MTA by refinancing the debt it accumulated after budget cuts. Arranged by Pataki’s friends, the “debt bomb” would later crush the MTA, while earning Pataki’s donors $85 million.

After Giuliani, billionaire Michael Bloomberg, a Democrat-turned-Republican (and if you kept track, later turned into an Independent-turned-Democrat), became mayor in 2002. Bloomberg both won the election thanks to Giuliani’s support and built off of his tenure as mayor. Ironically, the two later found themselves on opposite sides, as Giuliani became President Donald Trump’s top lawyer, and Bloomberg self-funded the most expensive presidential campaign ever to run as the Democrat against him (failing after spending $1 billion). One quote defined the tenure of Bloomberg more than all: “We love rich people.” Well-to-do New Yorkers had plenty to celebrate about Bloomberg’s run. To start, along with Governor Pataki, Bloomberg gave Henry Paulson and Goldman Sachs $1.65 billion in tax breaks. Why? To convince the company to build its new headquarters near Ground Zero, from their existing HQ in downtown a mile away. The luxury apartment boom has Bloomberg to thank and megaprojects such as the controversial Hudson Yards benefitted from over $6 billion in tax breaks. Bloomberg was quite successful in his courtship of fellow billionaires; New York became home to the most billionaires in the world.

“I think income inequality is a very big problem. But the bigger problem is, you can take money from the rich and move it over to the poor”

Former mayor Michael Bloomberg

For poor New Yorkers, the Bloomberg administration proved less generous. Homelessness rose in record numbers, something Bloomberg attributed to the fact “We have made our shelter system so much better that, unfortunately, when people are in it, or fortunately depending on what your objective is, it is a much more pleasurable experience than they ever had before.” 39% of affordable housing units were lost between 2002 and 2011. And the ~500,000 residents who live in NYCHA public housing projects would’ve loved to get its hands on $6 billion. In 2006, it was estimated that repairing all of the NYCHA units would cost around $6.9 billion. Instead, NYCHA public housing projects were the victim of disinvestment similar to the subway. Corners were cut, and over his tenure, tenant repair requests skyrocketed as the buildings began to crumble. By 2011, the estimate nearly more than doubled to $16.5 billion and there were 420,000 requests by 2012. It was then the Bloomberg administration set out to clear the backlog, forging signatures of tenants and secretly eliminating lead testing. There were tests revealing children living in NYCHA housing were exposed to lead at a level that could cause irreversible brain damage; yet for 20 years, the problems weren’t fixed, but rather were challenged. But officially, by the end of the Bloomberg tenure in 2013, backlog requests were down to 48,000. Bloomberg, the data-driven mayor, had deliberately manipulated it. Today, the NYCHA estimates that repairs will cost them at least $42 billion, more than six times of 2006.

The data manipulation extended into public schools. The schools were run like businesses, and test scores became the most important teacher and school evaluation tool. In 2009 it was announced that 82% of students passed math standards and about two-thirds passed reading, but in 2010, state officials announced the rise in test scores was misleading, as the tests became easier. The following year, more rigorous tests brought down scores to a 54% pass rate on math and 50% on English. Along with a controversial policy of shutting down the 100 worst-performing schools that led to mixed results and “shoddy oversight regarding high school graduation rates” leaves it unclear whether the public schools truly did improve under the Bloomberg administration.

But the controversy that bit Bloomberg during his 2020 run for president was his extensive use and previous defense of the policing strategy of “stop and frisk.” It gave police officers the authority to stop, question, and search civilians, but the ingrained racial bias disproportionately targeted young Black and Hispanic men, spiked. The stats were staggering, as the use of “stop and frisk” spiked, with about 85-87% of those stopped were Black or Latino (combined, the two groups made up 54% of NYC population in 2010) and nearly 9 out of every 10 people stopped were innocent. The policy was ruled unconstitutional, but the mayor and his police chief challenged the court ruling. It wasn’t until the next mayor that the practice would be largely ended.

“Ninety-five percent of murders- murderers and murder victims fit one M.O. You can just take the description, Xerox it, and pass it out to all the cops. They are male, minorities, 16-25. That’s true in New York, that’s true in virtually every city (inaudible). And that’s where the real crime is. You’ve got to get the guns out of the hands of people that are getting killed. So you want to spend the money on a lot of cops in the streets. Put those cops where the crime is, which means in minority neighborhoods. So one of the unintended consequences is people say, ‘Oh my God, you are arresting kids for marijuana that are all minorities.’ Yes, that’s true. Why? Because we put all the cops in minority neighborhoods. Yes, that’s true. Why do we do it? Because that’s where all the crime is. And the way you get the guns out of the kids’ hands is to throw them up against the wall and frisk them”

Michael Bloomberg on “stop and frisk”

Many felt that de Blasio’s nearly 50 point victory in the 2013 election had brought in a new era for New York. In some ways it did. His campaign, built upon progressive ideals and prominently featuring his biracial family, struck a chord with minorities and the working people who long felt overlooked by Bloomberg’s administration. Under the new de Blasio administration, Universal Pre-K and after-school care, mandatory paid sick leave, free school lunch, and a minimum wage increase to $15 are among the campaign promises that he delivered upon. The crime rate continued to go down underneath de Blasio even after he ended “stop and frisk,” proving it to simply be a racist, ineffective policy that eroded trust between police and minority communities, an assessment the National Review agreed to. New York was doing as good as it had ever been.

However, the realities of being mayor of New York City quickly set in. New Yorkers love to hate their mayors (evidenced by Koch, Dinkins, Giuliani, and Bloomberg all having had approval ratings in the 30s, even in the 20s), and it doesn’t help that de Blasio grew up a Red Sox fan, was caught eating pizza with a fork, accidentally dropped (and perhaps, killed) a groundhog, insisted on working out at his old Brooklyn gym, and is known as somewhat of an embarrassing dad figure.

But in all seriousness, why did de Blasio, who was re-elected handily in 2017, become so unpopular? A longshot 2020 presidential run didn’t help, but much of that narrative has been shaped by who he’s unpopular with. White voters throughout his tenure have consistently disapproved of him, especially with the “cocktail party circuit.” But the “tale of two cities” narrative continues to his popularity, as his African-American support ranges between steady to immensely popular. This is not to say all the criticism of de Blasio has been unfair. Beyond the petty and the media narrative (a two-way street of hate), were a few major problems. Affordable housing continues to be a polarizing issue, even as $238 million apartments fly off the market. School segregation persists, but his integration plan was divisive and shut down by the state. The subway and NYCHA public housing projects are in crisis, succumbing to two decades of deprivation and neglect, hurt even more by Superstorm Sandy in 2012. The complicated relationship between the city, state, subways, and NYCHA, along with de Blasio’s feuds with Governor and fellow Democrat Andrew Cuomo have strained progress. (It also doesn’t help the subway when Cuomo diverted MTA funds to bail out three ski resorts after a warm winter…) As de Blasio has said, he could not “put forward a plan that says we’re going to instantly wipe away 400 years of American history.” Indeed, fixing the system has proven quite difficult.

Amidst the dark days of New York, Andrew Cuomo’s father, former NY Governor Mario Cuomo took the stage at the 1984 Democratic National Convention. In response to then-President Ronald Reagan, he delivered an impassioned speech, ranked the 11th greatest speech by American Rhetoric. The elder Cuomo stated, “the President is right. In many ways, we are a ‘shining city on a hill.’ But the hard truth is not everyone is sharing in this city’s splendor and glory…In fact, Mr. President, this is a nation — Mr. President you ought to know that this nation is more a ‘Tale of Two Cities’ than it is just a ‘Shining City on a Hill.’”

More than 30 years later, the late Governor’s words ring truer than ever. New York has long been built upon racism, one where Jim Crow-era policies still reverberate through the spine of the city. The reality is that we live in an America where redlining still exists and school segregation persists, where African-Americans families have a net worth one-tenth of white families. It is a system that deliberately destroyed even a chance at the American Dream for so many Americans, simply for the color of their skin. The coronavirus pandemic has only magnified the divide, as America wakes up to a system that runs on the backs of the working class, but leaves it the most vulnerable. As 40% of low-income workers lost their jobs in March alone, billionaires in America have seen their wealth increase by a staggering $565,000,000,000 ($565 billion) during the pandemic, about ~20% each and growing. On top of this, the recent murders of innocent African-Americans, such as George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery are only the latest examples of a prejudiced system only now being rawly exposed by social media, sparking widespread outrage and protests. Whether you approve or disapprove of Mayor de Blasio, whether you agree or disagree with de Blasio’s policies, de Blasio was correct in his assessment of New York City and America: it truly is a “tale of two cities.”

“Ultraliberal New York had more integration problems than Mississippi. The North’s liberals have been for so long pointing accusing fingers at the South and getting away with it that they have fits when they are exposed as the world’s worst hypocrites.”

Malcolm X

Next, read my features: Gentrification before Gentrifications: The (Upper) West Side Story and Catalysts of Change: Chelsea Markets + High Line

For those interested in the topics discussed in this article:

- “One Mile” from Robert Caro’s The Power Broker

- The story of a homeless girl in New York; “Invisible Child” from the NYTimes

- “How Politics and Bad Decisions Starved New York’s Subways” from the NYTimes

- Watch “How Did New York’s Trains Get so Bad?” from the New York Times Youtube

- NYTimes article on NYC public schools

- NYTimes “The Weekly” feature on school segregation

- Marc Levin’s film Class Divide

- “The Rise and Fall of New York Public Housing” from the NYTimes

Kai Oishi

Evolution of NYC