It is hard to imagine a New York City without a Central Park. The truth was the creation of Central Park was far from inevitable. In 1811, the city released the Commissioner’s Plan, outlining the grid that defines Manhattan today. The most striking part of the plan is the lack of Central Park, though it included smaller squares and such to break up the grid.

The New York of the first half of the 19th century was one that was densely packed within Lower Manhattan. The streets were clogged with horse-drawn streetcars and horse waste, making crossing a street a perilous journey. The young city had some squares and open spaces, most notably Battery Park on the very southern tip of the island, but overall, the city was an unhealthy, crowded mess.

Though New York abolished slavery relatively early, the slow phase out of slavery, along with the city’s strong ties with the South meant even free African Americans were persecuted and limited to miserable living conditions.

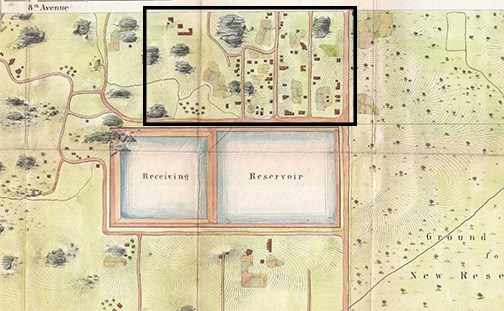

So came Seneca Village. Owning the land between present-day 83rd and 89th Street around the western edge of Central Park was the Whitehead family, who subdivided their land into 200 lots in 1825. This area was far from the bustle of downtown, rural in every sense. In the following 7 years, about half of the lots were sold to free black men, among them Andrew Williams, a shoe shiner, and Epiphany Davis, a store clerk. For free African Americans, Seneca Village provided the opportunity to truly live freely amongst each other. Residents could have gardens and livestock, with fish from the Hudson to boot, while a spring provided fresh water for the community, rarity in those days.

As racial tensions escalated in the city, especially in the notorious Five Points neighborhood, Seneca Village grew in size and reputation as a safe haven. By 1855, there were 3 churches, a school, and cemetery, along with nearly 300 residents. Seneca Village was not exclusively a black neighborhood though; nearly a third of residents were Irish, fleeing from the Great Potato Famine. Seneca Village was a rare example of an integrated community, where over half of African Americans owned property. Owning property even allowed a select few black men to vote.

The idea of a big, central park was gaining steam throughout the 1840s and early 50s, as affluent residents wanted a fashionable place to promenade. Some had eyed the parks of London with envy, wanting to replicate it back home. The first proposal for a park was between 66th and 75th Street on the Upper East Side in Jones’s Wood. It was controversial, as it was small (160 acres) and the wealthy Jones and Schermerhorn families who owned the land were able to reject the plan, and the courts ruled the proposal to acquire the land unconstitutional. Later, John Rockefeller would acquire this land, eventually turning the farms and orchards into the Upper East Side.

The elites then turned their eyes to the much larger 750 acre plot from 59th to 106th Street, between 5th and 8th Avenue, centered around the Croton Reservoir. The only problem? Small settlements, such as Seneca Village, lay in the way. Despite Seneca Village being home to many middle-class African Americans, it was portrayed as a squatter town filled with shanties by newspapers and politicians, allowing for the land to easily be condemned and cleared. Construction on Central Park began in 1857, as Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux began implementing their vision of a grand centerpiece of New York.

Today, Central Park is the crown jewel of New York, an unusually large urban oasis to provide respite from the buzz of the big city. Looking back, Seneca Village was just a small sacrifice for the greater good. It was also the start of a trend where the city displaced its African American residents, a city that has sadly become one of America’s most unequal and segregated.

Kai Oishi

Evolution of NYC